The domestic pig, also called puerco (pl.: pig) or domestic pig, is a domesticated, omnivorous mammal with smooth hooves. It is called the domestic pig to distinguish it from other members of the genus Sus. Some experts believe it is a subspecies of Sus scrofa (Eurasian wild boar or wild boar), while others believe it is a distinct species. Pigs were domesticated in the Neolithic period in East Asia and the Middle East. When domestic pigs arrived in Europe, they interbred extensively with wild pigs but retained their domestic characteristics.

Pigs are raised primarily for their meat, called pork. The hide or skin of the animal is used for leather. China is the world’s largest producer of pork, followed by the European Union and the United States. About 1.5 billion pigs are raised each year, producing about 120 million tons of meat, often salted as bacon. Some are kept as pets.

Pigs have been present in human culture since the Neolithic, appearing in art and literature for children and adults, and in cities like Bologna they are famous for their meat products.

Description

The pig has a large head, with a long snout strengthened by a special prenasal bone and a disk of cartilage at the tip.[2] The snout is used to dig into the soil to find food and is an acute sense organ. The dental formula of adult pigs is 3.1.4.33.1.4.3, giving a total of 44 teeth. The rear teeth are adapted for crushing. In males, the canine teeth can form tusks, which grow continuously and are sharpened by grinding against each other.[2] There are four hoofed toes on each foot; the two larger central toes bear most of the weight, while the outer two are also used in soft ground.[3] Most pigs have rather sparsely bristled hair on their skin, though there are some woolly-coated breeds such as the Mangalitsa.[4] Adult pigs generally weigh between 140 and 300 kg (310 and 660 lb), though some breeds can exceed this range. Exceptionally, a pig called Big Bill weighed 1,157 kg (2,551 lb) and had a shoulder height of 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in).[5]

Pigs possess both apocrine and eccrine sweat glands, although the latter are limited to the snout.[6] Pigs, like other “hairless” mammals such as elephants, do not use thermal sweat glands in cooling.[7] Pigs are less able than many other mammals to dissipate heat from wet mucous membranes in the mouth by panting. Their thermoneutral zone is 16–22 °C (61–72 °F).[8] At higher temperatures, pigs lose heat by wallowing in mud or water via evaporative cooling, although it has been suggested that wallowing may serve other functions, such as protection from sunburn, ecto-parasite control, and scent-marking.[9] Pigs are among four mammalian species with mutations in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor that protect against snake venom. Mongooses, honey badgers, hedgehogs, and pigs all have different modifications to the receptor pocket which prevents α-neurotoxin from binding.[10] Pigs have small lungs for their body size, and are thus more susceptible than other domesticated animals to fatal bronchitis and pneumonia.[11] The genome of the pig has been sequenced; it contains about 22,342 protein-coding genes.[12][13][14]

-

Skeleton

-

Skull

-

Bones of the foot

Taxonomy

The pig is most often considered a subspecies of wild boar, named Sus scrofa by Carl Linnaeus in 1758; therefore, the official name for the pig is Sus scrofa domesticus.[16][17] However, in 1777, Johann Christian Polycarp Erxleben classified the pig as a separate species from the wild boar. He gave it the name Sus domesticus, which is still used by some taxonomists.[18] The American Society of Mammologists considers it a separate species.[19]

Domestication

Archaeological evidence indicates that pigs were domesticated from wild boars in the Near East in or around the Tigris basin,[21] being kept in a semi-feral state, much as they are by some modern inhabitants of New Guinea.[22] Pigs were present in Cyprus by over 11,400 years ago, having been introduced from the mainland, meaning that domestication took place on the neighbouring continent at that time.[23] Pigs were separately domesticated in China around 8,000 years ago.[24][25][26] In the Middle East, pig farming became widespread over the following millennia. It gradually disappeared during the Bronze Age, as rural populations concentrated instead on market production, but persisted in cities.[27]

Domestication did not involve reproductive isolation with population bottlenecks. Pigs from West Asia were brought to Europe, where they interbred with wild boars. Interbreeding with a now-extinct population of feral pigs appears to have occurred in the Pleistocene. Domestic pig genomes show strong selection for genes influencing behavior and morphology. Human selection for domestic traits likely counteracted the homogenizing effect of wild boar gene flow and created islands of domestication in the genome.[28][29] Pigs arrived in Europe from the Middle East at least 8,500 years ago. Over the next 3,000 years, they interbred with European wild boars until their genomes showed less than 5% Middle Eastern ancestry, while retaining their domesticated characteristics.[30]

DNA evidence from subfossil remains of Neolithic pig teeth and jaws shows that the first domestic pigs in Europe were introduced from the Middle East. This stimulated the domestication of local European wild boars, leading to a third domestication event in which Middle Eastern genes disappeared from the European pig herd. In recent times, complex exchanges have taken place in which European breeding lines have been exported to the ancient Near East.[31][32] Historical records indicate that Asian pigs were reintroduced to Europe in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

HISTORY

Columbian Exchange

Among the animals introduced by the Spanish to the Chiloé Archipelago during the Columbian Exchange in the 16th century, pigs were the most adapted to local conditions. The pigs benefited from the abundance of shellfish and seaweed exposed by the archipelago’s high tides.[33] Pigs were brought from Europe to southeastern North America by de Soto and other early Spanish explorers. Escaped pigs became feral.

Feral Pigs

Pigs have escaped from farms and become feral in many parts of the world. Feral pigs from the southeastern United States have migrated north to the Midwest, where many state agencies have implemented culling programs. Feral pigs in New Zealand and northern Queensland have caused significant environmental damage.[38][39] Hybrids of wild European wild boars and domestic pigs disrupt both the environment and agriculture by destroying crops, spreading animal diseases, including foot-and-mouth disease, and eating wildlife such as young seabirds and turtle hatchlings.[40] Feral pig damage is a particularly serious problem in southeastern South America.

REPRODUCTION

Physiology

Female pigs reach sexual maturity between 3 and 12 months of age and enter estrus every 18 to 24 days if they are not successfully bred. Variation in ovulation frequency can be attributed to internal factors such as age and genotype, as well as external factors such as nutrition, environment, and exogenous hormone supplementation. The gestation period lasts an average of 112 to 120 days.[43]

Piglets warm togetherEstrus lasts two to three days, and the female’s willingness to mate is known as standing estrus. Standing estrus is a reflex response that is stimulated when a female comes into contact with the saliva of a sexually mature boar. Androstenol is one of the pheromones produced in the submandibular salivary glands of boars that trigger a response from the female.[44] A female’s cervix contains a series of five interlocking pillows, or folds, that hold the boar’s corkscrew-shaped penis in place during copulation.[45] Females have a bicornuate uterus, and to become pregnant, two embryos must be present in both uterine horns.[46] The mother’s body recognizes that she is pregnant between days 11 and 12 of pregnancy, which is marked by the corpus luteum producing the sex hormone progesterone.[47] To maintain the pregnancy, the embryo signals the corpus luteum using the hormones estradiol and prostaglandin E2.[48] This signal acts on both the endometrium and luteal tissue to prevent corpus luteum regression by activating genes responsible for maintaining the corpus luteum.[49] During mid- to late pregnancy, the corpus luteum relies primarily on luteinizing hormone for its maintenance until birth.[48]

Archaeological evidence shows that medieval European pigs farrowed or gave birth to a litter of piglets once a year.[50] By the 19th century, European piglets were routinely producing two litters of piglets per year. It is unclear exactly when this change occurred.[51] The maximum lifespan of pigs is approximately 27 years.

Nest-building

What pigs have in common with carnivores is nest building. The sow roots into the ground to create depressions the size of her body, then builds nesting mounds using twigs and leaves, softer on the inside, in which she gives birth. When the mound reaches the desired height, the sow places large branches, up to 2 meters long, on the surface. She enters the mound and digs it to create a depression in the collected material. She then gives birth in a lying position, unlike other hoofed ungulates, which usually stand upright during birth.[53]

Nest building occurs in the last 24 hours before the onset of parturition and becomes more intense 12 to 6 hours before parturition.[54] The sow separates from the group and looks for a suitable nesting site with well-drained soil and shelter from rain and wind. This provides the offspring with shelter, comfort and thermoregulation. The nest provides protection from the elements and predators while keeping the piglets close to the sow and away from the rest of the herd. This will prevent them from being trampled and other piglets from stealing the sow’s milk.[55] The onset of nest building is triggered by an increase in prolactin levels, caused by a decrease in progesterone and an increase in prostaglandins; collection of nest material appears to be further regulated by external stimuli such as temperature.[54]

Feeding and lactation

Pigs have complex feeding and suckling behaviours.[56] Feeding occurs every 50–60 minutes and the sow requires stimulation from the piglets before expressing milk. Sensory cues (vocalizations, odors from the mammary gland and birth fluids, and the sow’s coat patterns) are particularly important immediately after birth in helping piglets locate their teats.[57] Initially, piglets compete for position at the udder; piglets then rub their nipples with their snouts while the sow grunts at slow, regular intervals. Each series of grunts varies in frequency, pitch, and volume, indicating the piglets’ stages of suckling.

The teat competition and udder sniffing phase lasts about a minute and ends when milk begins to flow. Piglets then hold the teats in their mouths and suckle with slow mouth movements (one per second) and the rate of the sow’s grunts increases for about 20 seconds. The peak of grunting in the third suckling phase does not coincide with milk ejection, but rather with the release of oxytocin from the pituitary gland into the bloodstream.[59] The fourth phase coincides with the period of main milk production (10–20 seconds), when piglets suddenly withdraw slightly from the udder and begin suckling, making rapid mouth movements of about three per second. During this phase, the sow grunts more rapidly, more quietly, and often in rapid bursts of three or four. Eventually, the flow stops and with it the sow’s grunting. Piglets may roll from nipple to nipple and suckle again with slow movements or touch the udders. Piglets massage and suckle the sow’s nipples after the milk flow stops to inform the sow of her nutritional status. This helps her regulate the amount of milk released from that nipple during future sucklings. The more intense the nipple massage after suckling, the more milk the nipple will release later.[60]

Sows typically have 12 to 14 teats.

Sows typically have 12 to 14 teats.

Sow with suckling piglets

Sow with suckling piglets

Nipple order

Dominance hierarchies in pigs are formed at a very young age. Piglets are precocious and try to suckle shortly after birth. Piglets are born with sharp teeth and fight over the front nipples because they produce more milk. Once this nipple order is established, it remains stable; each piglet tends to feed on a particular nipple or group of nipples.[53] Stimulation of the anterior nipples appears to be important in eliciting milk flow,[61] so it may be beneficial for the entire litter if these nipples are occupied by healthy piglets. Piglets locate nipples by sight and then by smell.

Top Eight Major Swine Breeds

Berkshire

The third-most recorded breed of swine in the United States, Berkshires are known for fast and efficient growth, reproductive efficiency, cleanness and meat flavor and value. The first U.S. meeting of Berkshire breeders and importers was held in 1875, with the American Berkshire Association formed shortly after – making it the oldest swine registry in the world.

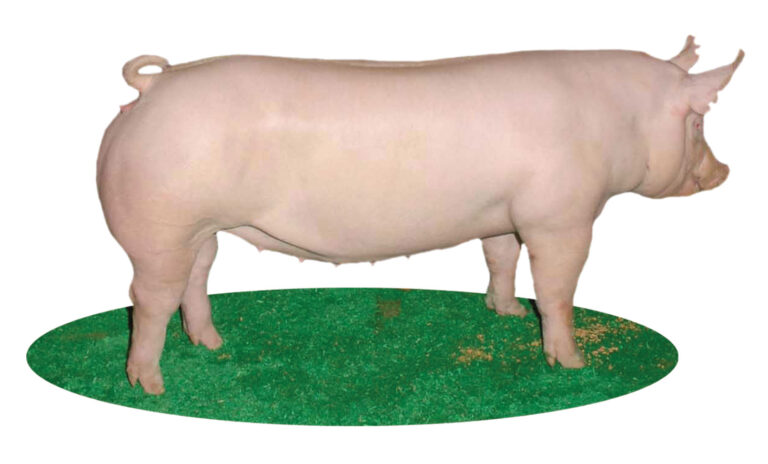

Chester White

Chester Whites originated in Chester County, Pa., from which their name was formed. These white hogs with droopy, medium-sized ears are known for their mothering ability, durability and soundness. Packers also tout their muscle quality.

Duroc

The second-most recorded breed of swine in the United States, the red pigs with the drooping ears are valued for their product quality, carcass yield, fast growth and lean-gain efficiency. They also add value through their prolificacy and longevity in the female line. Much of the U.S. breed improvement has occurred in Ohio, Kentucky, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa and Nebraska.

Hampshire

The hogs with “the belt,” Hampshires are the fourth-most recorded breed in the United States. Most popular in the Corn Belt, Hampshires are known for producing lean muscle, high carcass quality, minimal backfat and large loin eyes. Females also are known for their mothering ability, with longevity in the sow herd.

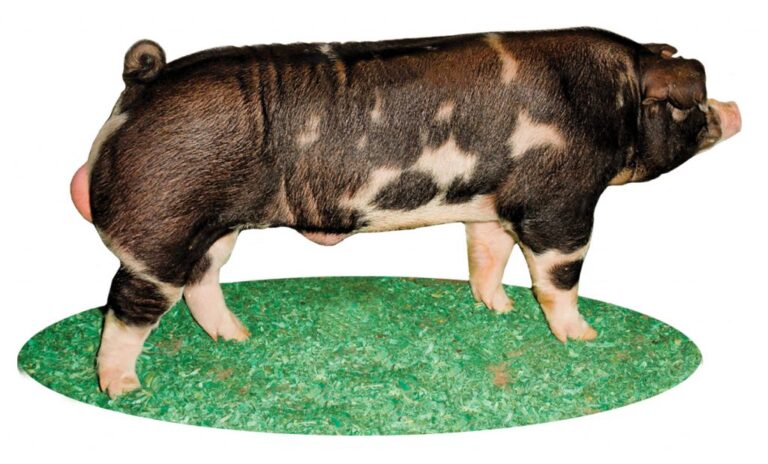

Spotted

The Spotted swine breed is characterized by large, black-and-white spots. Many breeders in central Indiana specialized in breeding Spotted hogs through the years. Today, Spots are known for their feed efficiency, rate of gain and carcass quality. In addition, commercial producers appreciate Spotted females for their productivity, docility and durability.

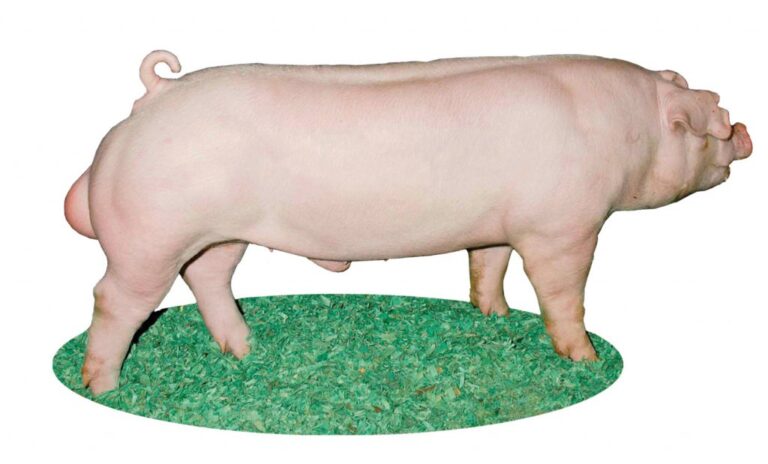

Yorkshire

The most-recorded breed of swine in North America, Yorkshires are white with erect ears. They are found in almost every state, with the highest populations being in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Nebraska and Ohio. Yorkshires are known for their muscle, with a high proportion of lean meat and low backfat. Soundness and durability are additional strengths.